Executive Summary

Over the past few months, we investigated cryptocurrency investment scam campaigns that combined two distinct fraud models: malvertising, which typically directs victims to fake investment platforms, and pig butchering, a scam that relies heavily on social engineering to gradually extract larger and larger sums of money from each victim over time. Evidence indicates the campaigns heavily target users in Asia, especially Japan. The financial impact can be significant, with individual victim losses related to this campaign alone of up to ¥10 million (approximately US$63,000) according to a December 2025 report by the Japanese television and radio broadcaster RCC Chugoku Broadcasting.

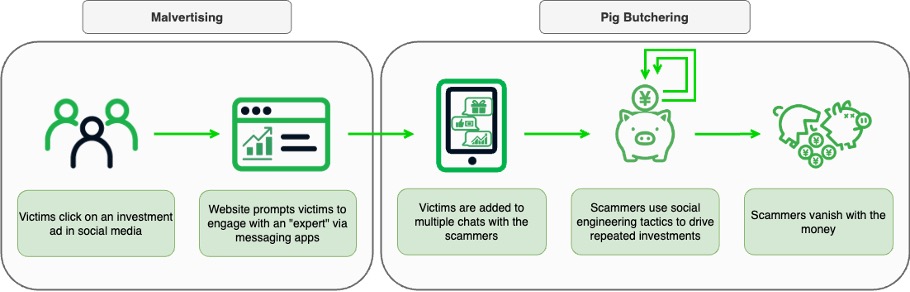

Our investigation began with the discovery of a cluster of suspicious domains—many generated using registered domain generation algorithms (RDGAs)—that were disproportionately queried by users in Japan. While we expected to uncover a classic investment scam, we discovered something quite different: a hybrid scam model that combines malvertising‑driven victim acquisition with messaging app‑centric pig butchering (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Hybrid use of malvertising and pig butchering

In these campaigns, ads impersonate well‑known financial experts or promote access to the “best” investment AI algorithm. These ads send users to websites that further redirect them to popular messaging apps. Once engaged, victims who have clicked on a legitimate messaging app link or scanned the official QR code, are drawn into one‑on‑one and group chats with AI bots that impersonate these experts, or often their assistants, and provide constant interaction, share fabricated success stories, and offer incentives such as gifts or rewards. Over time, they persuade victims to commit progressively larger amounts of money, culminating in a final demand for a so‑called “release fee” to unlock profits (which do not exist).

After pivoting on our initial DNS findings, we identified multiple interconnected campaigns and ultimately discovered more than 23,000 domains within this ecosystem. Although these campaigns may be operated by different actors, similarities in the underlying website framework along with overlapping advertising flows, analytic identifiers, and messaging‑based social engineering patterns suggest the presence and use of a shared enablement layer, potentially an as‑a‑service model or off‑the‑shelf kit.

To understand the campaigns more deeply, we engaged with the actors. We found that the chat groups had continuous engagement across time zones and a lack of disruption when conversations inadvertently changed language, strongly suggesting the use of automated or AI‑assisted chat systems, rather than a typical human‑driven interaction. In this blog, we’ll share our experience with the threat actors, as well as the DNS findings.

In addition to being a novel combination of malvertising and pig butchering, these campaigns may point toward how automation and AI‑assisted tooling could influence the future of social engineering to enable fraud. If this model were to be further developed, it could transform pig butchering from a high‑profit but labor-intensive operation into a faster, cheaper, and more globally scalable form of investment fraud.

From Malvertising to Messaging Apps

Cryptocurrency investment scams have long followed two familiar playbooks. In one, threat actors rely on malvertising, using social media ads, spam, or sponsored search results to push victims toward fake trading platforms designed to extract funds with the promise of high returns. In the other, pig butchering scams unfold more slowly, using prolonged and highly personalized social engineering techniques, typically via text messages and messaging apps, to encourage victims to invest progressively larger sums over time.

Both approaches are well documented, widely reported, and certainly familiar to us as a research team. We have previously studied each in depth, including our recent work on the booming pig butchering‑as‑a‑service (PBaaS) economy, as well as earlier research on many malvertising actors leveraging different DNS techniques for their campaigns, including Savvy Seahorse, who uses DNS CNAMEs and Facebook ads to lure victims to fake investment platforms. We’ve also documented other actors using Facebook ads and bulk domain registration, as well as lookalike domains used in AI-produced videos on hacked YouTube channels.

Over the past several months, however, we began to observe campaigns that no longer fit neatly into either category. What started as a DNS‑led investigation into suspicious domains disproportionately queried by users in Japan revealed a growing number of investment scams that effectively blend both approaches to scamming into a single operation.

Rather than using malvertising solely to direct victims to fraudulent investment platforms, these campaigns use it as an initial acquisition channel, redirecting users to “lure websites” where they are prompted to initiate contact through popular messaging applications, either by clicking on a legitimate messaging app link or scanning an official QR code. It is within these messaging apps that the social engagement phase, and ultimately the fraud itself, takes place.

This shift changes both the scale and the mechanics of these scams. Malvertising continues to provide reach and volume, while messaging apps offer a familiar and often trusted environment for sustained interactions. Together, they form a hybrid scam model that combines the efficiency and scale of malvertising with the psychological leverage of pig butchering.

These campaigns also use modified pig butchering techniques in an effort to better gain victims’ trust. Instead of scammers initiating contact, as is typical with these schemes, the workflow is structured so victims initiate each step of the scam themselves: clicking the ad, engaging with the lure website, and transitioning to the messaging application. This helps create an impression of voluntary participation rather than overt coercion.

RDGA Domains

Pivoting from the initial cluster of suspicious domains that triggered this investigation, we expanded our DNS analysis and identified thousands of additional domains associated with similar activity. A significant proportion of those appeared to have been generated using RDGAs, which are typically registered in bulk via APIs.

Threat actors use RDGAs to rapidly create and register large numbers of domains, reducing the time and effort required to scale their campaign infrastructure and allowing domains to be rotated in response to detection or takedown efforts.

While many of these RDGA domains consist of random character strings, others appear to have been created using brand‑related dictionaries to produce lookalike domain names. This is likely an attempt to make campaign-related domains such as googlenames[.]top and youtubefind[.]com appear familiar and legitimate, and therefore safe. When paired with social media advertising, these lookalike domains lower initial suspicion and increase the likelihood of victim engagement.

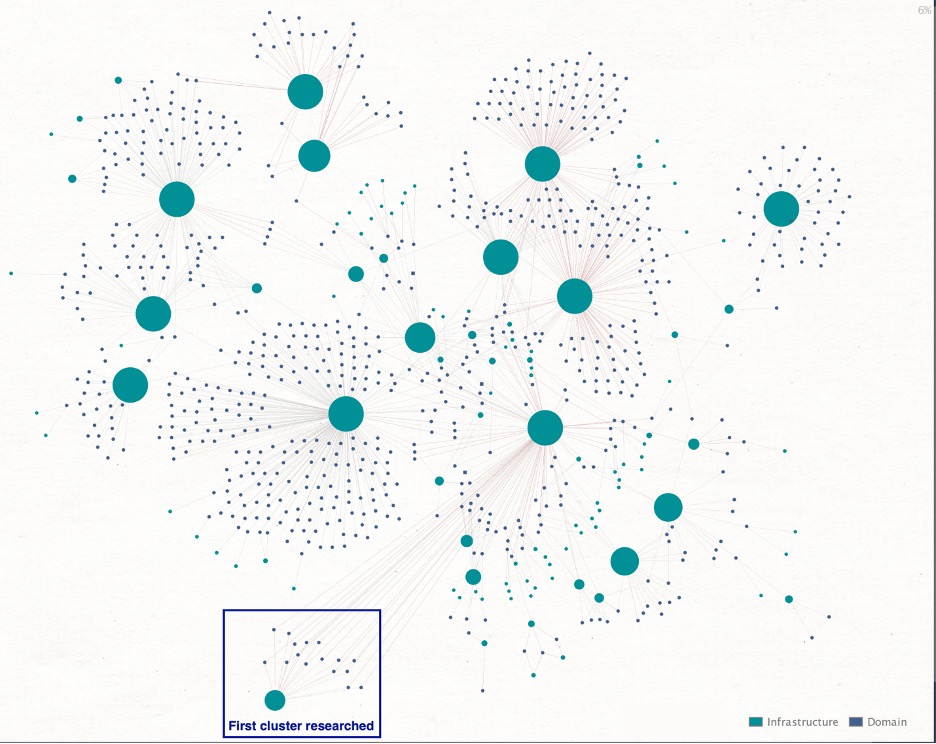

In addition to distinctive RDGA naming patterns, we used domain registration and DNS characteristics such as name server (NS) records, registrar selection, advertiser tracking IDs, and the autonomous system numbers (ASNs) associated with host IP addresses to identify more than 100 distinct clusters of domains associated with the same scam activity.

To illustrate the scale and complexity of these relationships, Figure 2 shows larger infrastructure nodes (combinations of registrars and name servers), along with the unique, smaller domain nodes associated with them.

Figure 2. Campaign-associated clusters comprised of infrastructure and domain nodes

The observed domain naming strategies correlate with domain longevity. Lookalike and dictionary-based domains often remain active for at least a year, whereas domains composed of random character strings are typically cycled out after approximately four months.

This pattern suggests a deliberate trade-off between domain credibility and disposability within the same operational model: higher-quality domain names seem to be reserved for longer-lived infrastructure while lower-effort domains appear to be treated as more disposable.

Although many of the identified domain clusters exhibit similar characteristics and are interrelated, there are clear differences in registrar usage, hosting providers and top-level domains (TLDs); see Table 1. This variation suggests distinct infrastructure choices, likely made by multiple operators, within a broader shared ecosystem.

| Top five TLDs | Sample domains | Targeted countries |

|---|---|---|

| .sbs |

fhysgth[.]sbs ghmfg[.]sbs hrdfsetsdf[.]sbs koaliuehudrt[.]sbs safesecurea[.]sbs |

Japan |

| .icu |

8jz2x[.]icu r2th4[.]icu ttrvsgg[.]icu ttrvsii[.]icu xqeha[.]icu |

South Korea United States |

| .top |

7973268[.]top googlenames.top xhlch[.]top yhdakgjd[.]top youtubefind[.]top |

Pakistan Singapore Turkey United Kingdom |

| .click |

aopmbxeqax[.]click gnlaoprs[.]click oiajdng[.]click vbmuakf[.]click ydfshans[.]click |

Japan Philippines |

| .buzz |

fgynfgi[.]buzz kpusnenvcg[.]buzz lgsmjhsb[.]buzz oslddjb[.]buzz stock-analysis06[.]buzz |

United States |

| Table 1. Top five observed TLDs | ||

The substantial volume of observed domains, the high frequency of new domain registrations and the diversity of supporting infrastructure are consistent with an industrial-scale deployment by multiple actors rather than a single small or localized campaign.

To date, we have associated more than 23,000 domains with this scam ecosystem, including instances where hundreds of domains were registered on a single day. Figure 3 illustrates a steady increase in registrations beginning in early 2025, punctuated by periodic spikes that align with intensified campaign activity in July and September.

Figure 3. Monthly distribution of second-level domain (SLD) registrations linked to these campaigns since January 2025

Website Lures

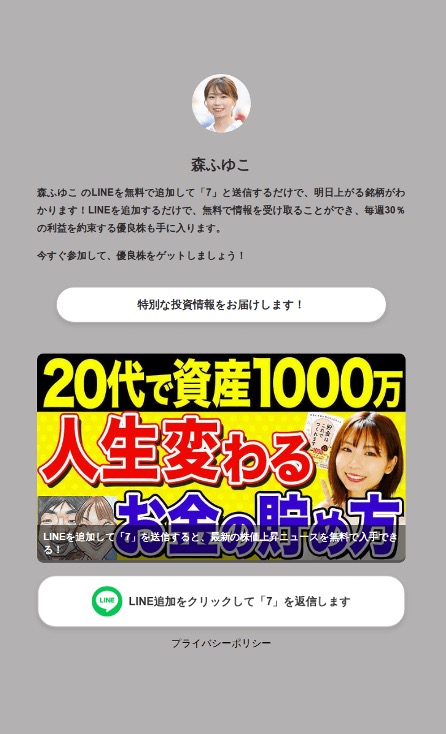

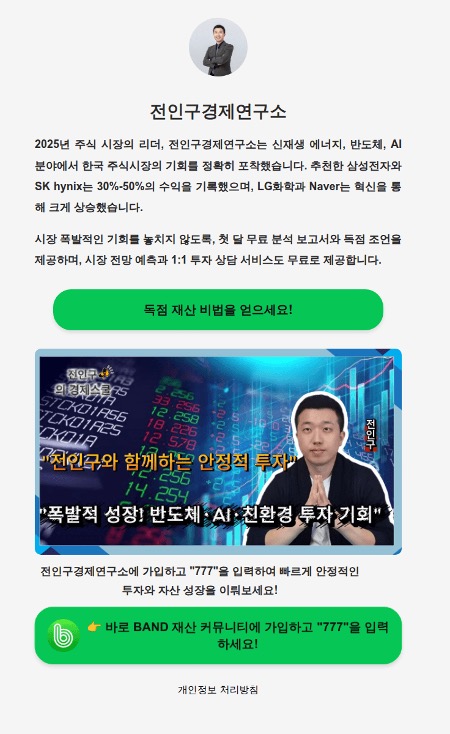

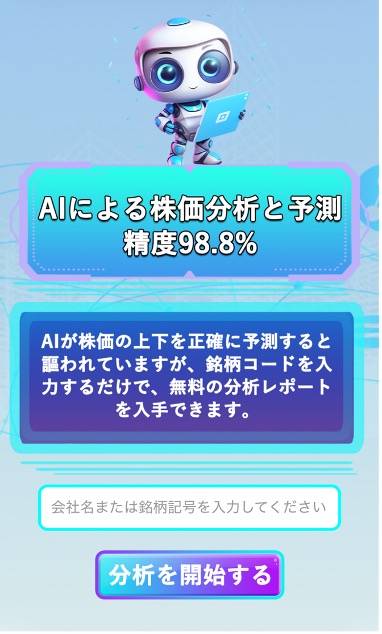

Upon investigation of the initial malvertising campaigns, we noted that the websites that were hosted on the domains we identified shared consistent layouts, messaging, and interaction flows. Across the large number of sites we analyzed, the underlying structure remained effectively unchanged, suggesting that they were generated from a common site framework or kit rather than being independently developed (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Structurally similar sites (Top: Financial expert variant; Bottom: AI algorithm variant)

These lure websites continue the narrative introduced by the initial malvertising messages to build credibility and trust by exploiting the likeness of the financial expert or offering access to the “best” investment AI algorithm.

The content of these sites is deliberately designed to prompt victim interaction through enticing language, eye‑catching visuals depicting potential investment results, and promises of free assistance, all leading to a clear call to action.

In some cases, visitors are directed to join an investment chat or community within a legitimate messaging app via a link or by scanning an official QR code (to facilitate access from mobile devices). In other cases, users are prompted to submit a company ticker symbol for “AI‑driven” analysis, reinforcing the illusion of legitimacy and credibility before being directed to the investment chats and communities.

Regardless of the interaction mechanism used, the role of these sites is to transition curious potential victims from the initial ad and into a familiar messaging app so that the “personal” interaction phase of the scam can begin.

We were able to use the domains identified during our DNS analysis to compile a catalog of structurally similar scam websites across multiple campaigns and regions.

Evidence of the repeated use of the same underlying framework, especially across otherwise distinct domain clusters, further supports the likelihood of there being a shared enablement layer that underpins most, if not all, of this activity.

Regional Targeting and Persona Impersonation

While Japanese journalists have reported on individual scams and the tens of thousands of yen lost by the victims, these incidents have largely been treated as isolated cases. However, we have been able to piece together a much broader picture by clustering the identified domains and correlating shared characteristics across campaigns.

Geographically, Japan has been the primary target and Asia has been the most heavily impacted region. That being said, the underlying threat appears to be increasingly global in scope. We detect an average of 4,000 RDGA‑generated domains per month tied to these campaigns, and they are active worldwide.

The lures in these Japanese campaigns follow the same patterns described in our April 2025 blog, which detailed common investment scam tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). Specifically, these campaigns use social media ads on platforms such as Instagram and Facebook, promising high returns and free investment advice while exploiting the likenesses of well‑known financial experts, including:

- Takaaki Mitsuhashi, a Japanese economic commentator and YouTuber with more than 905,000 subscribers

- Mori Fuyuko, an investment YouTuber with more than 650,000 subscribers

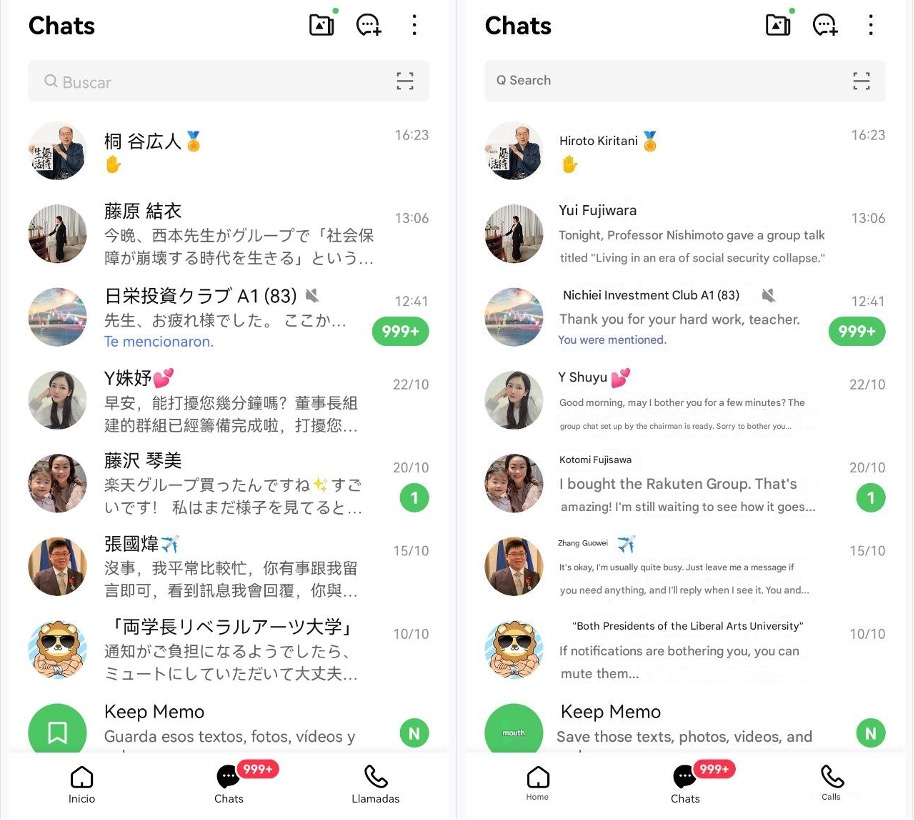

- Hiroto Kiritani, a Japanese millionaire widely known as the “God of Freebies”

- Nam Seok‑kwan, a prominent figure in the Korean investment industry

- Chang Kuo‑wei, president of StarLux Airlines

Several of these individuals have publicly addressed the malicious campaigns abusing their likenesses, warning audiences about the associated risks and decrying the harm being caused to their reputations.

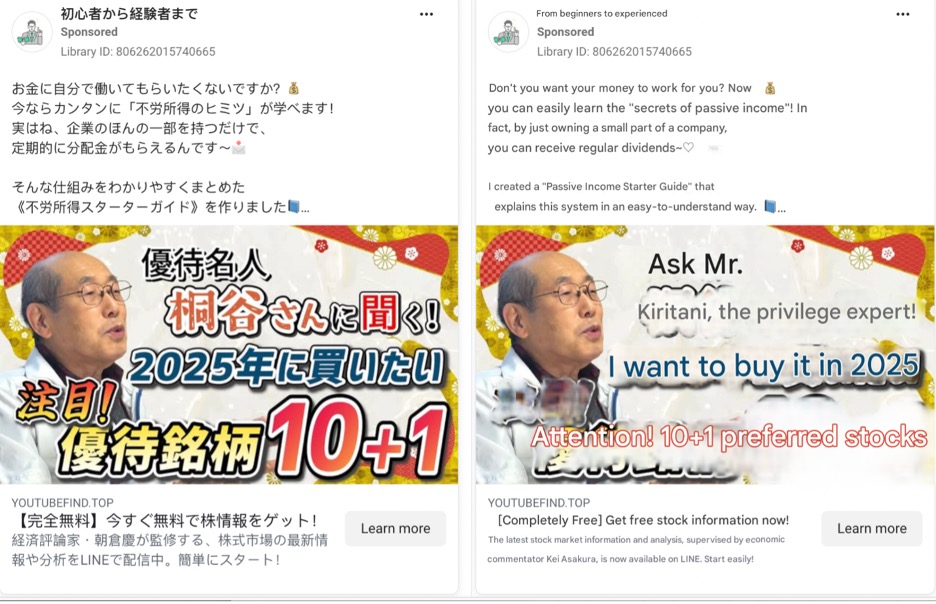

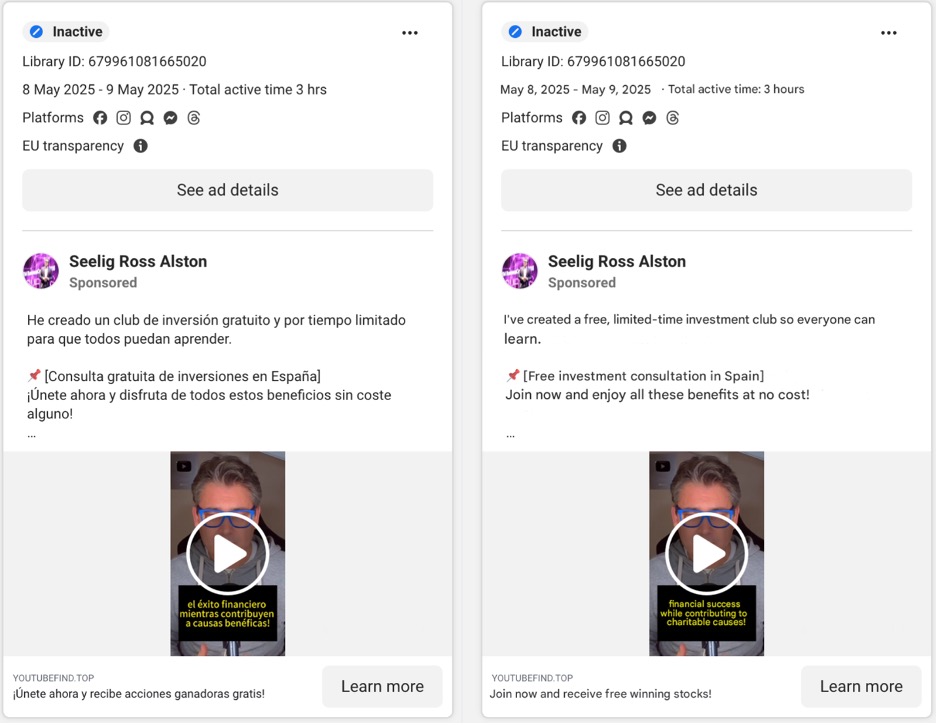

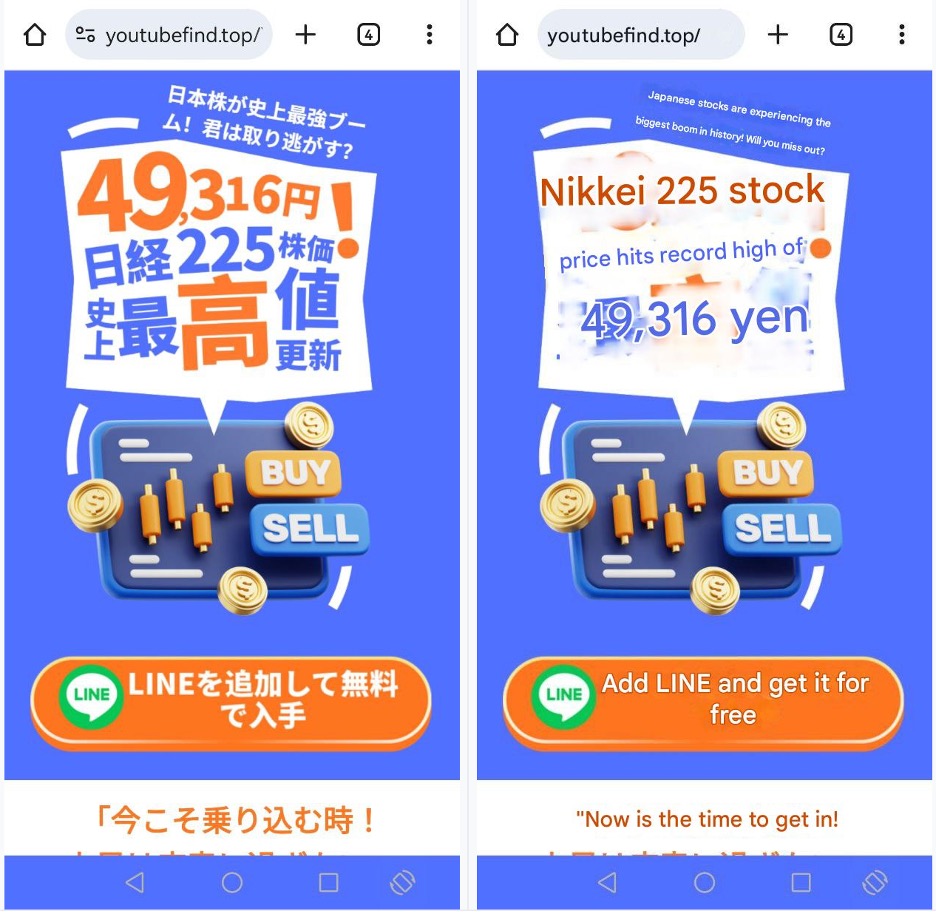

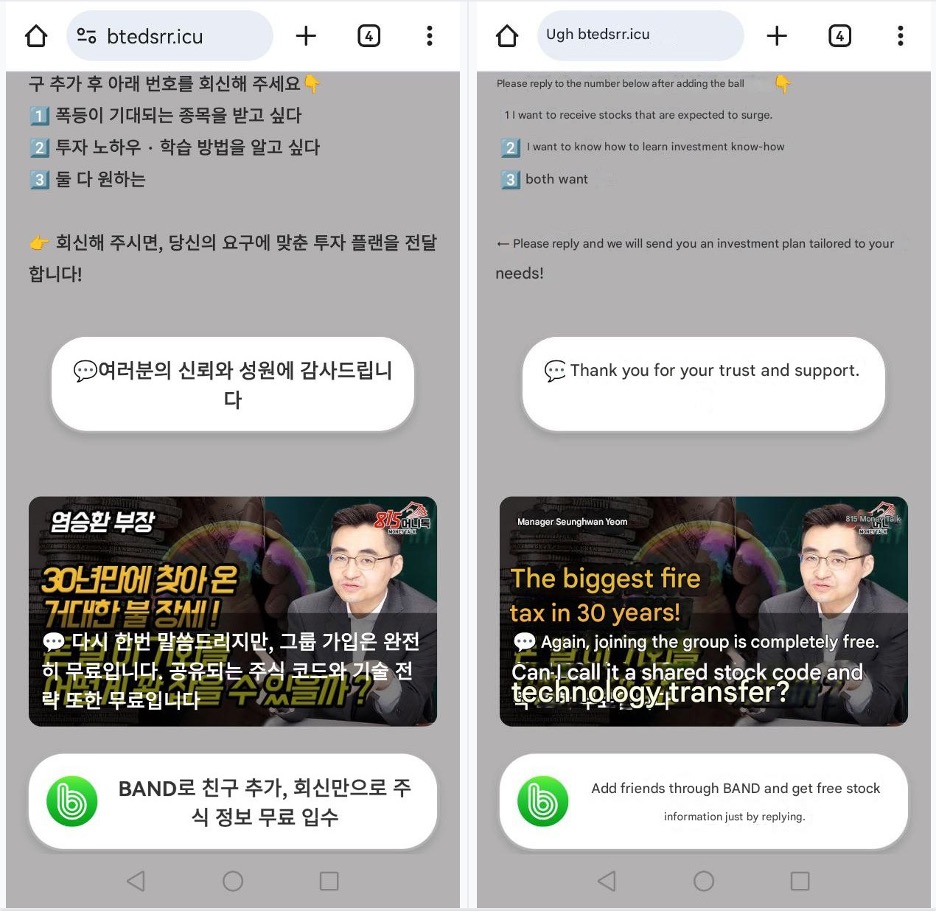

Further highlighting similarities across campaigns, a recent social media ad observed on Meta targeting Japanese speakers and misusing the likeness of Hiroto Kiritani (Figure 5) reuses youtubefind[.]top, a lure domain that was also used in an older campaign that targeted Spanish speakers (Figure 6).

Figure 5. Ad on Meta targeting Japanese speakers, misusing the likeness of Hiroto Kiratani, and directing to ‘youtubefind[.]top’ (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

Figure 6. Older ad on Meta targeting Spanish speakers, also directing to ‘youtubefind[.]top’ (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

While some of these ads were active for only a few hours, many remained online for considerably longer. Notably, even malicious ads that we directly reported to Meta as abusive remained online for approximately one week before any apparent enforcement action was taken.

These ads ultimately direct victims to actor‑controlled websites that form the next stage of the funnel. As shown in Figures 7 and 8, these sites are structurally similar and continue using the same persona as the ads to maintain the investment narrative before driving victims toward legitimate messaging apps such as KakaoTalk, LINE, and WhatsApp.

Figure 7. Actual destination of the ad shown in Figure 5 with the link to youtubefind[.]top (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

Figure 8. Destination website of a South Korean ad campaign (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

Chat Apps and AI Bots

Having encountered an active and ongoing campaign, we made the decision to engage directly, acting as scam bait, to observe and better understand how the fraud unfolds once victims are transitioned into messaging applications. From our resulting “victim experiences,” we confirmed that the TTPs were highly consistent across the campaigns we interacted with.

After clicking through the initial ad and following the flow from the lure website, we were directed into messaging applications, where it quickly became apparent that we were interacting with a chatbot rather than a human, and likely an AI‑driven one at that.

Following an initial one‑on‑one engagement with the impersonated “expert,” we were directed to a secondary chat with their “assistant.” From there, we were guided toward a larger “class group chat,” where a supposed teacher provided investment guidance and other “students, just like us” participated in ongoing daily discussions.

Figure 9 shows a snapshot of the many concurrent chats we became part of after engaging with only three campaigns.

Figure 9. Our “LINE” messaging app showing multiple scam chats and groups across three campaigns (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

Within these group chats, we received a steady stream of enticing messages, including promises of sky‑high profits from the “experts” and fabricated success stories shared by other “students.”

We were also offered a points-based incentive. The points would supposedly be redeemable for prizes (Figure 10) and awarded based on our continued engagement.

Figure 10. Pamphlet of incentive prizes shared during a chat session; we have our eyes on that massage chair! (Left: Original; Right: English translation)

We were encouraged to provide our thoughts on market‑related questions, such as “Do you think X stock will rise tonight?” or “Which currency should be exchanged for the yen: the euro or the dollar?” and share screenshots of our trading activity.

All these chats ultimately give the game away. Seemingly scripted chatter, recycled questions, and lightning‑fast responses at any hour all point toward automated, likely AI‑assisted behavior. While we cannot confirm that the same AI or chatbot system powers every campaign we observed, the consistency of interactions and account behaviors across campaigns strongly suggests the use of the same underlying ecosystem.

The apparent use of intelligent automated interactions demonstrates that pig butchering scams no longer require teams of human operators to maintain one‑on‑one conversations. Victims are effectively alone: there are no experts, no students, and no one gets to sit in that massage chair—except maybe the scammers.

We didn’t take the final step of the scam ourselves; instead, we relied on Japanese media reporting based on victim testimony to complete the sequence. According to these sources1,2 (one is geo-restricted to Japan), victims are first encouraged to deposit funds and make investments using legitimate applications and publicly traded stocks. Once a level of trust has been established, they are prompted to transfer money directly to the scammers, often under the pretext of earning extra profits.

Victims are then shown fabricated and exaggerated returns to give the illusion of success and encourage them to make further deposits. In reality, no investment activity takes place; the funds only enrich those behind the schemes. When the scammers decide to end the interaction, they inform victims that the service is shutting down and instruct them to pay a final fee to “release” their profits—the coup de grâce. By the time the deception becomes clear, the funds are long gone.

From Regional Threat to Global Model

While Japan and South Korea are among the most heavily impacted regions, campaigns associated with this ecosystem are increasingly targeting English-, German-, and Spanish‑speaking audiences. This shift suggests continued geographic expansion beyond the initial focus on Asia, likely enabled by infrastructure and workflows that are easily reused and localizable.

These campaigns demonstrate how pig butchering no longer needs to rely on labor-intensive, long‑con personal interactions. By combining malvertising‑driven victim acquisition with messaging‑centric pig butchering techniques, actors can now deploy scalable, automated business models that merge two previously distinct scam methods into a single operational workflow. The low cost of entry and ability to scale globally make this hybrid approach particularly attractive to cybercriminals and could point toward a meaningful shift in how investment fraud is conducted.

Indicators of Activity

A sample set of technical indicators associated with these campaigns is provided below; further indicators are available from our GitHub repository.

| Indicator | Description |

|---|---|

| 7973268[.]top | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign |

| 8jz2x[.]icu | Domain hosted an English scam campaign |

| aopmbxeqax[.]click | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Takaaki Mitsuhashi |

| btedsrr[.]icu | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign abusing the likeness of Seunghwan Yeom |

| fgynfgi[.]buzz | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| fhysgth[.]sbs | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Takaaki Mitsuhashi |

| ghmfg[.]sbs | Domain hosted an English scam campaign abusing the likeness of Andre Iguodala |

| gnlaoprs[.]click | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Kenichi Ohmae |

| googlenames.top | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| hrdfsetsdf[.]sbs | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| koaliuehudrt[.]sbs | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Yusaku Maezawa |

| kpusnenvcg[.]buzz | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| lgsmjhsb[.]buzz | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| oiajdng[.]click | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Ken Honda |

| oslddjb[.]buzz | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| r2th4[.]icu | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| safesecurea[.]sbs | Domain hosted a Japanese and Chinese scam campaigns abusing the likeness of Jen-hsun huang (Nvidia CEO) and masquerading as the International College of Liberal Arts (iCLA) |

| stock-analysis06[.]buzz | Domain hosted an English scam campaign |

| ttrvsgg[.]icu | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign abusing the likeness of a “Healing Traveler” YouTuber |

| ttrvsii[.]icu | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign abusing the likeness of a “Healing Traveler” YouTuber |

| ttrvsrr[.]icu | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign abusing the likeness of a “Healing Traveler” YouTuber |

| vbmuakf[.]click | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Ken Honda |

| xhlch[.]top | Domain hosted a Japanese AI investing scam campaign |

| xqeha[.]icu | Domain hosted a Korean scam campaign abusing the likeness of Seon Dae-in TV YouTuber |

| ydfshans[.]click | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Takaaki Mitsuhashi |

| yhdakgjd[.]top | Domain hosted a Japanese scam campaign abusing the likeness of Ken Honda |

| youtubefind[.]top | Domain hosted scam campaigns abusing the likeness of various individuals |